Middle East. ISIS, a history: how the world’s worst terror group came to be

TERROR. To understand the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria — why it exists, what it wants, and why it commits terrible violence of which the Paris attacks are only the latest — you need to understand the tangled story of how it came to be.

The group began, in a very different form, in 1999. In the 16 years since, it has been shaped by — and has at moments helped to shape — the conflicts, physical and ideological, of the Middle East.

Here, then, is a concise history of the rise of ISIS from its earliest origins to the present day. It is the story of one of the richest and most powerful terrorist organizations ever to exist — but it’s also a story that reveals the ways in which ISIS has proven much weaker than you might think.

1989–1999: The Soviet war in Afghanistan and the beginning of ISIS

(US Department of Defense/Getty Images)Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in Iraq.

You cannot understand ISIS without understanding al-Qaeda and the history they share, as well as the differences, there at the beginning, that would ultimately divide them. And al-Qaeda’s origin story begins with the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Soviet aggression shocked the Muslim world, galvanizing roughly 20,000 foreign fighters to help Afghans resist Soviet forces. That’s where Osama bin Laden met a number of other young radicals, who together formed the core of the al-Qaeda network.

The Soviets withdrew in 1988, but they left a puppet regime in place, and the war continued. The next year, a Jordanian man named Ahmad Fadhil Nazzal al-Khalaylah joined them.

Al-Khalaylah would, years later, achieve global infamy under his nom de guerre, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. He would found the group that became what we today call ISIS.

When Zarqawi first traveled to Afghanistan, in 1989, he wasn’t all that religious: He was, as Mary Anne Weaver writes in a definitive Atlanticprofile, something of a petty thug. But once there, he met a man named Sheikh Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, a leading proponent of violent, fundamentalist Islam. Maqdisi converted Zarqawi to his cause. Zarqawi would not meet bin Laden for years, and the two men built up allies and followers independently from each other — a dynamic that made Zarqawi’s network even more extreme than bin Laden’s.

« Whereas bin Laden and his cadre grew up in at least the upper middle class and had a university education, Zarqawi and those closest to him came from poorer, less educated backgrounds, » Aaron Zelin, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, writes. « Zarqawi’s criminal past and extreme views on takfir (accusing another Muslim of heresy and thereby justifying his killing) created major friction and distrust with bin Laden when the two first met in Afghanistan in 1999. »

2003–2009: The rise and fall of al-Qaeda in Iraq

Unidentified anti-American insurgents in northern Iraq in 2006.

Zarqawi returned from Afghanistan, and in 1999 in Jordan formed his own group, Jamaat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (JTWJ), or the Organization of Monotheism and Jihad. For the first few years, Zarqawi’s group was a bit player among jihadists, overshadowed by al-Qaeda. But this was the group, then little known, that would later become ISIS.

In 2003, the US led its invasion of Iraq and changed, in the world of jihadists, everything.

The American-led war, by destroying the Iraqi state, left much of the country in chaos. Foreign fighters and extremists began moving into Iraq, assisted by Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, which sought to bog down the US. Zarqawi and his group were among them.

The Sunni extremists who arrived found a friendly audience among former Iraqi soldiers and officers: The US had disbanded Saddam Hussein’s overwhelmingly Sunni army, which was disbanded in 2003, creating a group of men who were unemployed, battle-trained, and scared of life in an Iraq dominated by its Shia majority.

Zarqawi’s group, as it fought in Iraq, grew to prominence, attracting al-Qaeda’s attention. In 2004, Zarqawi pledged loyalty to al-Qaeda, for which he would receive access to its funds and fighters. His group was renamed al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), and it became the country’s leading Sunni insurgent group.

AQI didn’t just fight the Americans, it also attacked fellow Iraqis. It bombed Shia mosques and slaughtered Shia civilians, hoping to provoke mass Shia reprisals against Sunni civilians and thus force the Sunnis to rally behind AQI. It worked, and it’s a tactic ISIS still uses today. It also helped spark a civil war in Iraq between Sunnis and Shia.

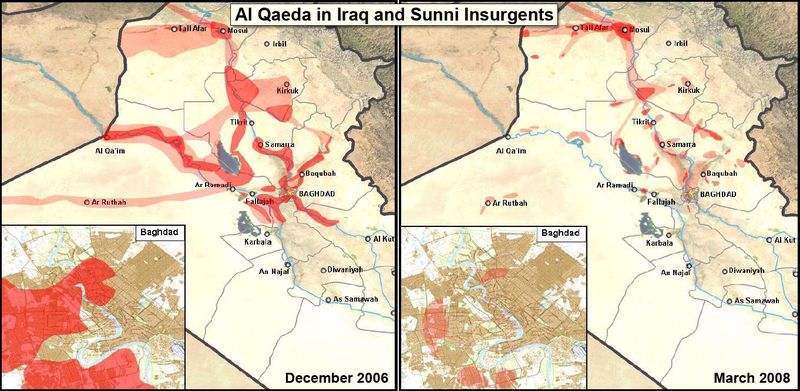

But these methods were too vicious even for al-Qaeda, which warned Zarqawi to cool it. He ignored the warnings, and AQI came to hold a swath of territory in Sunni parts of Iraq, roughly along the lines of what ISIS controls there today. Yet between 2006 and 2009, it all came crashing down:

(MNF-Iraq)Territory controlled by AQI and other Sunni insurgent groups.

Starting in 2006, AQI’s extremism began to backfire. Sunni tribal leaders, who had always hated living under AQI’s harsh and often violent rule,became convinced that the Shias were starting to win Iraq’s sectarian civil war. To avoid being on the losing end of a bloody war, they up took arms against AQI in a movement called the Awakening.

Zarqawi was killed in 2006 by a US airstrike, and the US increased its troop presence in Iraq that year and the next. But it was, more than anything else, the Awakening that defeated al-Qaeda in Iraq.

By 2009, almost all of AQI’s fighters were dead or in prison, and the group was a shadow of itself. But it had learned a valuable lesson: Dissent from Sunnis under its rule could be disastrous. That’s why, years later, ISIS has slaughtered members of Sunni tribes, such as Iraq’s Abu Nimr, en masse. It sees brutality as the best way to prevent a replay of the 2006 uprising that led to its downfall.

2010: Iraq begins unraveling, setting the stage for AQI’s comeback

(Sabah Arar/AFP/Getty Images)Former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki.

ISIS was able to rise from AQI’s ashes in no small part because of Iraq’s catastrophic internal politics.

« Iraq was the essential incubator, » according to Fred Hof, who for part of 2012 served as the Obama administration’s special adviser for the transition in Syria.

By 2010, « Iraq finally had relatively good security, a generous state budget, and positive relations among the country’s various ethnic and religious communities, » Zaid al-Ali, author of The Struggle for Iraq’s Future, wrote in Foreign Policy. But it was squandered. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki stripped political opponents of power, appointed his cronies to run the army, and killed peaceful protestors.

Most importantly, he reconstructed the Iraqi state on sectarian lines, privileging the Shia majority over the Sunni minority. This exacerbated Iraq’s existing sectarian tensions: Sunni Iraqis falsely believed themselves to be Iraqi’s majority (owing to Saddam-era propaganda) and saw Maliki as depriving them of their rightful control of the state. He only deepened their belief that the Iraqi state was fundamentally illegitimate.

By this time, al-Qaeda in Iraq had a new leader: Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, an Iraqi who had a background in serious religious scholarship. Under his leadership, AQI began allying with former officers from Saddam Hussein’s army and recruited disaffected Sunnis. Iraq’s own government, unintentionally, gave them exactly the opening they needed to regain strength.

« Raw political sectarianism in Iraq was the main causal factor [in ISIS’s rise], » Hof writes.

August 2011: AQI’s remnants move into Syria — with a little help from Assad

(John Cantlie/Getty Images)A Syrian rebel mourns the death of a comrade.

Around this same time, Syria erupted in Arab Spring protests that became a civil war. In March 2011, Syrian demonstrators took to the streets to demand Bashar al-Assad step down. Almost right away, the Syrian regime began slaughtering protestors in an attempt to provoke a civil war.

« It was very much a strategic decision that the regime made, to militarize the conflict right away, » Glenn Robinson, an associate professor at the Naval Postgraduate School, told me in a phone conversation. « I think, in their mind and correctly, if this becomes a political battle where populations matter, the regime probably only has support of a third of the country … the opposition has the numbers. »

Perhaps the most devious part of this strategy was Assad’s deliberate effort to promote Islamic extremism among the opposition. In amnestiesissued between March and October 2011, Assad released a significant number (exact counts are hard to know) of extremists from Syrian prisons. Hof called this an « effort to pollute the opposition with sectarianism »: Assad gambled that if his enemies were Islamic militants, then the West wouldn’t intervene against him.

In August 2011, Baghdadi sent a top deputy, Abu Mohammad al-Joulani, to Syria to set up a new branch of the AQI in the country. Joulani succeeded, establishing Jabhat al-Nusra in January 2012. Joulani’s fighters quickly proved themselves to be some of the most effective fighters on the Syrian battlefield, swelling their ranks with new recruits.

At this point, Baghdadi’s original group was still in Iraq alone. It had not become ISIS. But to understand how it did, you have to see the larger forces that opened his way.

Early 2012: Syrian jihadists get their « angel investors »

Today, ISIS is the world’s richest terrorist group, its funding coming mostly from various extortion schemes in the territory it controls. But back in 2012, foreign donations played a crucial role in growing the group from the poor organization it was then into the monster it is today.

In 2012, money flew into Syria from the Gulf Arab states — places like Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. The key investments in ISIS didn’t come directly from those countries’ governments, but rather from private individuals living there who wanted to see the Assad regime fall — and perhaps to promote extremism itself.

« These rich Arabs are like what ‘angel investors’ are to tech start-ups, except they are interested in starting up groups who want to stir up hatred, » former US Navy Admiral and NATO Supreme Commander James Stavridis told NBC last June. « Groups like al-Nusra and ISIS are better investments for them [than moderates]. »

Though these donors have since faded in importance, they were invaluable at the time. « The individuals, » Stavridis explained, « act as high rollers early, providing seed money. Once the groups are on their feet, they are perfectly capable of raising funds through other means, like kidnapping, oil smuggling, selling women into slavery, etc. »

But while the Gulf financiers’ intent may have been to hurt Assad, they actually ended up propping him up by playing into his strategy of promoting extremism.

« It was a service of incalculable value to the Assad regime: It enabled him to say — albeit inaccurately — that he was the alternative to terrorism and sectarianism, » Hof told me via email.

July 2012: The great ISIS prison break begins

(Wathiq Khuzaie/Getty Images) Iraq reopens Abu Ghraib in 2009. About four years later, ISIS would bust between 500 and 1,000 inmates out of here.

There’s one chapter of the story of ISIS’s rise that very rarely gets mentioned: its spectacular series of attacks on Iraqi prisons in 2012 and 2013. These prison breaks supplied it with a huge infusion of recruits, and also illustrates how effectively ISIS took advantage of the Iraqi government’s weakness.

In July 2012, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi released a statement to his loyalists. « We remind you of your top priority, which is to release the Muslim prisoners everywhere, » he said, « and making the pursuit, chase, and killing of their butchers from amongst the judges, detectives, and guards to be on top of the list. »

This was, unambiguously, a call to break former Iraqi insurgents out of jail — and ISIS followed their leader’s order. Over the next year, they attacked a number of prisons across Iraq, freeing somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,000 inmates.

These included, former CIA analyst Aki Peretz writes, « many terrorists [that] elite US military forces caught over the years and then handed over to the Iraqi government when the United States turned over custody of its prison facilities in 2010. »

People incarcerated for common crimes were also recruited. « Prisoners convicted of criminal charges provide advantages to the terrorist group, because they could have been recruited during their incarceration, » Peretz writes. « Even if common criminals were able to resist jihadist persuasion efforts while in prison, they may now feel indebted to their ‘liberators.' »

This won ISIS a rapid infusion of manpower — and also illustrates that well before the 2014 crisis, we had signs that the Iraqi state was falling apart in a way that would empower extremists. The ISIS crisis didn’t come out of nowhere, in other words: It was a slow motion disaster with plenty of advance warning.

April 2013: ISIS officially becomes ISIS — and divorces al-Qaeda

(ISIS) An ISIS fighter holds the group’s flag.

As all this was happening, Baghdadi’s organization was still named al-Qaeda in Iraq. But Baghdadi worried that Joulani — his commander of Jabhat al-Nusra, the group in Syria — was acting too independently and would quit AQI to make Jabhat al-Nusra a separate group.

In April 2013, Baghdadi did something dramatic: He asserted unilateral control over all al-Qaeda operations in both Syria and Iraq. To demonstrate this change, he renamed AQI « the Islamic State in Iraq and Greater Syria » — or ISIS, for short.

This didn’t sit well with Joulani, who appealed to al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Zawahiri, who’d never really trusted AQI, sided with Joulani — a decision that Baghdadi rejected. ISIS and al-Qaeda eventually split, dividing the jihadist movement in Syria.

This left ISIS to « gradually emerge as an autonomous component within the Syrian conflict, » Brookings Doha‘s Charles Lister writes, by absorbing Nusra fighters and territory in northern and eastern Syria. It ended up taking firm control of much of this territory, establishing a de facto capital in the northern city of Raqqa.

Assad, for his part, was perfectly happy to leave ISIS alone — particularly as it primarily fought other rebel groups. « ISIS almost never fought the Assad regime, » Robinson says. « They were much more focused on fighting other opposition groups and gaining land their opponents had already acquired. »

By February 2014, Zawahiri had had enough. He formally exiled ISIS from al-Qaeda, leading to what Zelin describes as « open warfare in Syria » between the groups. Today, the groups continue to struggle over territory and ideological control over the global jihadist movement.

This dynamic, in part, drives ISIS’s brutality: One of the group’s key means of capturing foreign fighters’ hearts and minds is through public, over-the-top slaughter that wins their attention.

June 2014: ISIS sweeps northern Iraq and declares a caliphate

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

This is the moment when everything that had happened before in ISIS’s rise came to a head. On June 10, 2014, a force of about 800 ISIS fighters defeated 30,000 Iraqi government troops to capture Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city. In the next two days, ISIS fighters swept through Iraq’s heavily Sunni northwestern and central provinces — coming, at their peak, extremely close to Baghdad.

This blitzkrieg built on months of ISIS momentum. In January, ISIS had seized control of Fallujah, a former AQI stronghold in western Iraq. The Iraqi government’s repeated inability to retake Fallujah in the following months illustrated the depleted and incompetent state of the Iraqi army after years of Maliki’s mismanagement.

The conquest of Mosul and much of northern Iraq led a triumphant Baghdadi to declare his territory a « caliphate » on July 4. By this, Baghdadi meant that ISIS was now a state — and not just any state but the only Islamically legitimate state in the world. All Muslims, Baghdadi said, were obligated to support the nascent Islamic state in its struggle to hold and expand its land.

Establishing a caliphate had long been the goal of the entire jihadist movement. By declaring that he had actually created one, Baghdadi gained a huge leg up on al-Qaeda in the struggle for global jihadist supremacy.

Since then, ISIS has « succeeded in attracting far, far more recruits » than al-Qaeda, Will McCants, the director of the Brookings Institution’sProject on US Relations With the Islamic World, told me. This has also has allowed it to gain a following among foreign terrorist groups, with major ISIS franchises in Libya, Egypt’s Sinai desert, and Nigeria.

But ISIS had also taken a task with burdens beyond what it can perhaps sustain. By committing to actually governing a swath of territory in Syria and Iraq as a state, ISIS couldn’t rely purely on insurgent tactics or hiding among civilians. It needed to engage in pitched conventional battles to defend its land.

« When they declared the caliphate, their legitimacy came to rest on the continuing viability of their state, » Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, told me last October. In the coming year, this would prove to be a serious problem for the group.

August 2014: ISIS makes its first huge mistake — invading Kurdistan

(John Moore/Getty Images_A Kurdish fighter near the front lines with ISIS in 2015.

Ever since its AQI days, ISIS had been prone to ideological and political overstretch.

« To be the caliph, one must meet conditions outlined in Sunni law, » Graeme Wood explains in an excellent Atlantic feature on ISIS’s theology. One condition is that « the caliph have territory in which he can enforce Islamic law. » Once the caliphate is established, « the waging of war to expand the caliphate is an essential duty of the caliph. »

Everything we know about ISIS suggests that both its fighters and Baghdadi himself earnestly believe this. This is what led them to attack Iraq’s Kurds.

Iraq’s Kurdish minority controls a semi-autonomous region in northeastern Iraq, and has a powerful military force known as the peshmerga. For the first half of 2014, they had been content to sit out the ISIS conflict.

But in August 2014, ISIS decided to invade Iraqi Kurdistan, quickly advancing to within several miles of the capital, Erbil. It also launched a genocidal campaign against a minority group known as the Yazidi, who are ethnically Kurdish.

This brought the peshmerga into the war, which have since dealt ISIS a series of stinging defeats. It also drew the United States into the war: President Obama’s bombing campaign against ISIS initially began as a limited intervention to protect American personnel in Erbil and stem the slaughter of the Yazidis.

ISIS’s progress into Kurdistan was reversed. Pressed by Kurds, a regrouping Iraqi military, Iranian-backed Shia militias, and US aircraft, ISIS began to fall back. By early 2015, ISIS began taking losses: The heavily Sunni city of Tikrit fell to Iraqi forces in April.

« The Islamic State … will lose its battle to hold territory in Iraq, » Douglas Ollivant, the former national security adviser for Iraq under both George W. Bush and Obama, wrote in War on the Rocks this February. « The outcome in Iraq is now clear to most serious analysts. »

June 2015: ISIS’s capital comes under threat

(Institute for the Study of War)A map of the battle lines in northern Syria circa June 25. Notice how close Kurdish positions are to Raqqa.

In Syria, things had long looked better for ISIS than they had in Iraq: the multi-sided civil war meant that there was no unified, reliable force to challenge them. But in mid-2015, Syrian Kurds began threatening ISIS’s territory.

ISIS, as in Iraq, had attempted to invade and conquer the territory within Syria that is dominated by Kurdish groups — and came damn close. In October 2014, ISIS nearly seized Kobane, a Kurdish stronghold on Syria’s northern border with Turkey.

But the Kurds held out for months. In January, aided by US support and US-led coalition air strikes, they pushed ISIS out of Kurdish territory. Then they kept going, seizing ISIS territory elsewhere in Syria. They advanced to within 30 miles of ISIS’s de facto capital at Raqqa.

The Soufan Group, a private intelligence firm focusing on terrorism, described the Kurdish-led advance on Raqqa as the « most serious symbolic and meaningful threat [to ISIS] since it declared itself a caliphate almost one year ago. »

These Kurdish victories showed that ISIS was running up against the limits of its military strategy. Since last June, the group has been fighting too many enemies on too many different fronts. Its ability to maneuver rapidly around its territory has been limited by coalition airstrikes. Slowly but steadily, it has been losing ground.

ISIS « lost something like 25 percent of their territory » since its peak last summer, McCants says.

Autumn 2015: ISIS turns to international terrorism

(Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)Mourners across from the Bataclan concert hall in Paris.

On November 13, terrorists attacked several locations around Paris, killing more than 130 and wounding more than 380. ISIS claimed responsibility, and the French government has said that it believes the group was responsible.

So why, as it slowly loses ground in Iraq and Syria, bit by bit losing the caliphate that has been its primary focus, might ISIS be sending fighters abroad at this critical moment?

ISIS thrives on a narrative of victory. In order to sell itself as the prophesied return of the caliphate, it needs to show that its victories are inevitable and divinely inspired. If it’s losing territory, then it needs to sell its narrative through other means. That means claiming « victory » over foreign enemies by hitting them with terrorist attacks. Indeed, Paris wasn’t the only foreign attack ISIS has launched: ISIS suicide bombers have hit Kuwait, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia. It also claimed responsibility for taking down a Russian civilian airliner in Egypt’s Sinai desert.

« Much of ISIS’s ideological support and recruiting strength emanates from a narrative that it is victorious, » J.M. Berger, the co-author of ISIS: A State of Terror, explains via email. The Paris attack « changes the conversation from ‘ISIS is contained’ on November 12 to ‘ISIS is rampaging uncontrollably’ on November 14. »

Moreover, ISIS may believe that terrorist attacks are its best way of striking back against — and maybe, it believes, deterring — foreign attacks. (The French are part of the US-led coalition bombing ISIS in Syria and Iraq). That conclusion would likely be wrong, but ISIS may still believe it.

« I think it has made the calculation that it can no longer pursue its expansion strategy in Syria and Iraq without changing the calculations of the enemies currently halting its expansion, » McCants says. « These attacks would be a way of inflicting costs on them. »

But here’s one final scary twist: ISIS may not have planned it at all. The attack could have been independently undertaken by European ISIS sympathizers or veterans rather than planned from ISIS HQ in Raqqa.

This would be yet another stage in ISIS’s evolution: an inspirational symbol for wannabe terrorists around the world.

« If they’re not even trying to coordinate this kind of stuff, and their affiliates or fan boys can do it on their own, it’s quite troubling, » McCants concludes.