Weather. Extreme heat, cold and rainfall make January a month of extremes.

HOT The importance of accurate and timely forecasts and investment in early warning systems has once again been highlighted by extreme weather which wreaked a heavy economic, environmental and human toll throughout January 2026.

National Meteorological and Hydrological Services have been on the frontline, with intense heat and fire, record-breaking cold and snow, devastating rainfall and flooding impacting countries in every region of the world.

The WMO Coordination Mechanism has ensured the provision of expert advice to humanitarian agencies, curating information from WMO Members and Centres. Authoritative warnings and information on potentially high-impact weather, water, and climate events are all centrally available at the WMO message format designed for all media, all hazards, and all communication channels via the Common Alerting Protocol.

“It is no wonder that extreme weather consistently features as one of the top risks in the The World Economic Forum’s flagship annual Global Risks Report. The number of people affected by weather and climate-related disasters continues to rise, year by year, and the terrible human impacts of this have been apparent on a day-by-day basis this January,” said WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo.

“This is what drives us to expand and accelerate the Early Warnings For All initiative because disaster-related deaths are six times lower in countries with good early warning coverage,” she said.

Long-term temperature increase is fueling more frequent extreme weather. WMO recently confirmed that 2026 was one of the three warmest years on record.

Extreme Heat and Wildfires

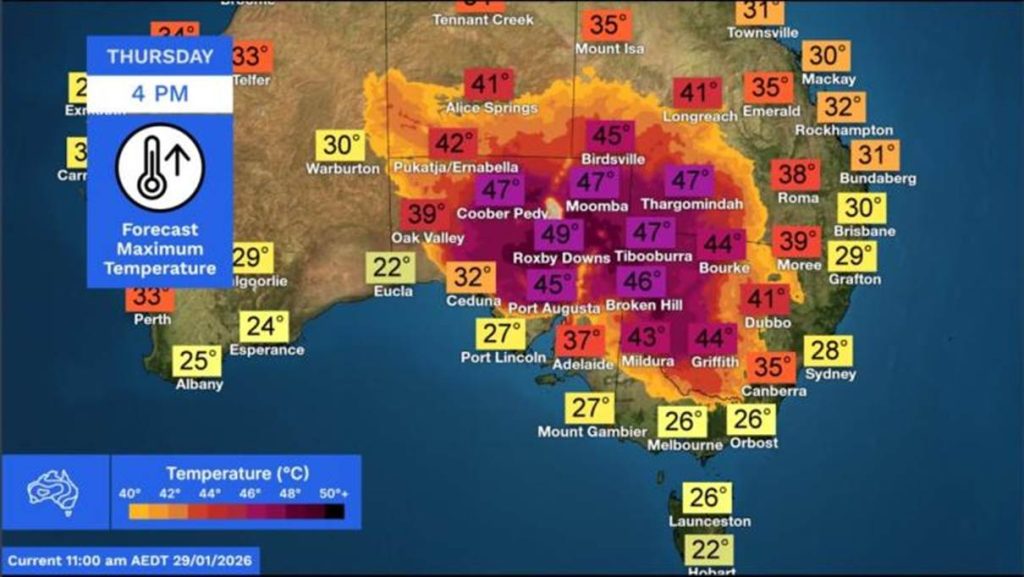

Large parts of Australia have been gripped by two heatwaves in January, with dangerous fire weather conditions.

The town of Ceduna in South Australia reached 49.5°C on 26 January – a new record for that location, whilst few other places around South Australia, north-west Victoria, inland New South Wales and south-west Queensland peaked above 45 °C, according to the Bureau of Meteorology.

Australian authorities issued heatwave warnings, with clear messaging which is a critical component of saving lives and protecting people’s health against what is often known as the silent killer.

The fire danger ratings were ranked as high to extreme because of the combination of heat and gusty winds, including across Victoria, which was hit by large bushfires earlier.

The late January heatwave was the second to hit Australia in less than a month. World Weather Attribution scientists combined the observation-based analysis with climate models to quantify the role of climate change in the 5-10 January event and concluded that climate change made the extreme heat about 1.6°C hotter.

Bureau of Meteorology, Australia

In Chile, deadly wildfires burned across Biobío and Ñuble regions, forcing tens of thousands to evacuate, destroying hundreds of structures and resulting in at least 21 fatalities. A state of catastrophe was declared as 75 separate fires spread under extreme heat and wind.

In Southern Argentina, high temperatures, prolonged drought and strong winds combined to fuel devastating fires in Patagonia.

According to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), human-caused climate change has increased the frequency and intensity of heatwaves since the 1950s and additional warming will further increase their frequency and intensity.

WMO is stepping up action on extreme heat and heatwaves, including through a new framework and toolkit to help countries strengthen governance, coordination and investment in response to extreme heat risks. It has a Climate and Health Joint Office with the World Health Organization and is one of the co-sponsors of the Global Heat-Health Information network.

It is also working with Members and partners to develop a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary global strategy to strengthen wildfire early warning and advisory services.

Extreme cold and winter storms

The frequency and intensity of cold extremes have decreased on the global scale since 1950, according to the IPCC, and average winter temperatures have been rising. However, long-term global climatic trends do not eliminate the occurrence of extreme weather or regional cold spells.

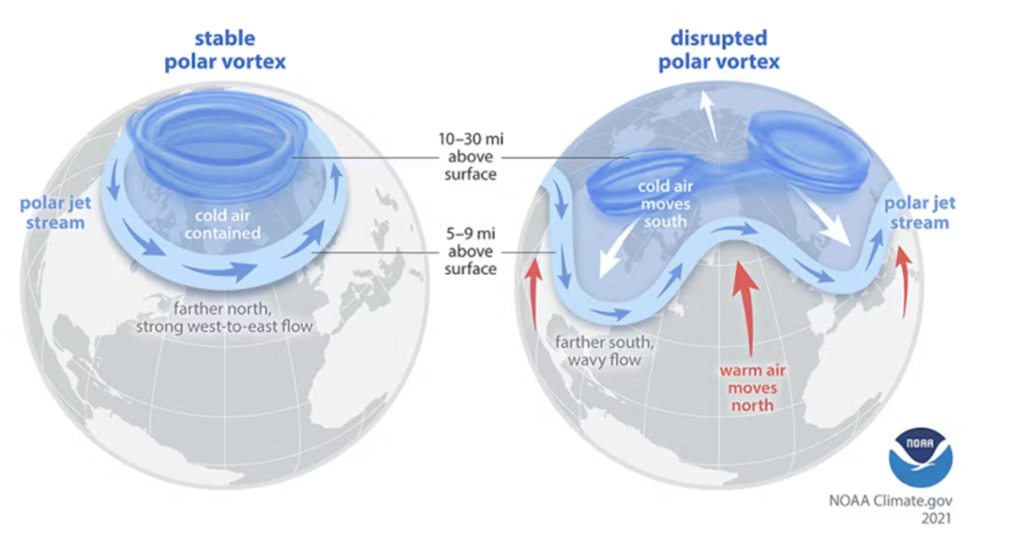

A weakened and distorted polar vortex, which caused extra waviness in the polar jet stream, helped fuel extensive intrusions of frigid air into the mid-latitudes, contributing to cold snaps in North America, Europe, and Asia, and priming the atmosphere for disruptive winter storms in January.

The polar vortex is a massive river of cold air and strong winds that typically circles the North Pole. When it weakens, Arctic air spills southwards and warmer air is sucked into the Arctic.

Some meteorological forecasts indicated that a major sudden stratospheric warming event over the Arctic could cause significant weakening of the polar vortex in early February, setting the scene for a further risk of Arctic air intrusion into North America and northern Europe later in February.

Prevention WEB/NOAA

North America: In the last week of January, a massive winter storm crossed much of Canada and the USA, dropping widespread snow, sleet and freezing rain and bringing life-threatening cold and ice. Massive flight cancellations and power outages affected hundreds of thousands of households and there were a number of deaths.

The US National Weather Service warned that another blast of Arctic air would surge south down the Plains, across the Great Lakes and through the Southeast and East by 31 January.

“This could be the longest duration of cold in several decades,” it said, warning of dangerously cold temperatures into early February – in addition to yet another winter storm hitting the weekend of 31 January.

Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula received more than 2 meters of snow in the first two weeks of January, following 3.7 meters in December. Together, these totals make it one of the snowiest periods the peninsula has seen since the 1970s, according to Kamchatka’s Hydrometeorology Center. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, the regional capital, came to a standstill, with reports of large snowdrifts burying cars and blocking access to buildings and infrastructure.

WMO’s Coordination Mechanism, in its Global HydroMet Weekly Scan (WCM-GWS) on 22 January advised of very heavy rainfall and snowfall, with the risk of floods and avalanches, in northern Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and western Nepal.

Europe: Large parts of Europe witnessed back-to-back storms, with heavy precipitation, strong winds and high waves causing travel disruption and flooding in many countries, ranging from Ireland and the United Kingdom in the west to Portugal and Spain and the entire Mediterranean region.

National Meteorological and Hydrological Services issued multiple alerts warnings, including top-level danger to life warnings.

The Deutscher Wetterdienst, which is one of WMO’s regional climate monitoring centres in Europe, issued an updated climate watch advisory on 27 January on above average precipitation over parts of Greenland, Northwestern and Western Europe, and the Mediterranean region in the next two weeks. Absolute weekly precipitation totals will be mostly 25–100 mm, in exposed places locally above 100 mm, it said in its guidance to NMHSs.

It said that Arctic cold air will spread again especially in Northern and Northeastern Europe in the next weeks. The affected areas include Norway, Sweden, Finland, European Russia (north), Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus (north).

Heavy rainfall and flooding

WMO’s Coordination Mechanism, in its Global HydroMet Weekly Scan on 22 January, advised of continued very heavy rain in south-eastern Africa where weeks of downpours have swollen rivers and overwhelmed key reservoirs, sending floodwaters spilling into heavily populated areas.

Mozambique was worst hit. Flooding has affected at least 650,000 people, displaced hundreds of thousands, and destroyed or damaged at least 30,000 homes, according to Mozambique’s National Disasters Management Institute, though it’s likely the numbers will increase due to ongoing search and rescue operations. Some of the hardest-hit cities include the capital Maputo.

Crops have been destroyed and livestock killed, and there is an elevated risk of cholera and other water-borne diseases, said the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

South Africa declared a national disaster on 18 January over torrential rains and floods that have killed at least 30 people and washed away homes, roads and bridges in the country’s north – which is next to Mozambique.

A World Weather Attribution Study said that climate change and La Niña combined to create ‘perfect storm’ in the deadly Southern Africa floods in Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Eswatini.

The study, which involved climate scientists from National Meteorological Services in the region, said the intensity of heavy downpours has increased by 40% since preindustrial times, with some areas receiving over a year’s rain in just days.

Mozambique is a champion of the Early Warning For All initiatives, with a national roadmap which seeks to ensure a coherent and consolidated Multi-Hazard Early Warning System program embedded into its five-year development plan. South Africa also has a national Early Warnings For All roadmap, in recognition of the importance of early warnings in saving lives, property, critical infrastructure and supporting sustainable development.

In Indonesia, more than 50 people were killed in a landslide in West Java on 24 January. It was triggered by heavy rainfall but the underlying causes of the tragedy was a more complex risk equation including geological characteristics, slope gradients, soil stability, and unsustainable land-use practices.

In New Zealand, a series of tropical storm systems brought record rainfall to the upper North Island, triggering flooding and landslides that caused casualties at a campsite.